L. Frank Baum

Baum’s work had been adapted to stage and screen a handful of times before the film company was formed. The Selig Polyscope company had created the single reel “The Wonderful World of Oz” a few years earlier, and prior to that, Baum had toured the country with a stage/magic lantern/live reading presentation of his stories called “The Fairylogue and Radio-Plays.” The film, however, had little input from Baum himself and was still rather primitively made. It simply didn’t do justice to his work.

Scene from "The Wonderful Wizard of Oz"

Taking that to heart, and seeing an opportunity to create Oz films under his direct supervision, Baum announced the formation of the Oz Film Company in mid-1914. Baum told the trade magazines that his goal was to produce fairy tales and family-oriented entertainment that would delight parents and children alike without the threat of inappropriate content. Baum told Moving Picture World that he formed the company after “realizing the tremendous field open to a company producing quaint fairy stories full of clean comedy, love and adventure, teeming with transformations, illusions, appearances and disappearances.”

Oz Film Co main building

Shortly after the formation was announced, a state-of-the-art studio was erected in Santa Monica. Moving Picture World boasted that the studio was beautiful and had all of the modern conveniences one could imagine. The sets and scenery, too, were well-crafted, with papier mache props giving a charming touch to the fairy stories. The company intended to “produce all of the fairy tales including some of the famous stories like ‘The Wizard of Oz,’ ‘The Patchwork Girl,’ ‘The Tik Tok Man,’ and many others equally as fascinating,” and decided to start with “The Patchwork Girl.”

Scene from "The Patchwork Girl" featuring Pierre Couderc

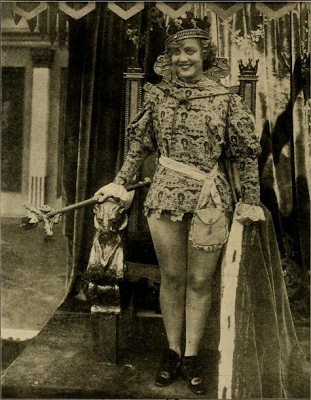

“Patchwork Girl” was a recent release in the Oz novel series, and had only been around for a year when Baum originally decided to turn it into a stage play. But the idea was abandoned with the formation of Oz Film and it was adapted once again, this time for the screen. In July, it was announced that producing director J. Farrell MacDonald had begun work on “Patchwork.” He was a respected name, and had a number of credits already under his belt as both a director and an actor. He would later go on to star in many westerns, most notably under the direction of John Ford. There were many unknowns working under Baum who would soon become stars in their own right, including Violet MacMillan, Harold Lloyd and Hal Roach. The company was so confident in its longevity and success that two other productions were also planned and well into production by the time “Patchwork” was released in September -- “The Magic Cloak of Oz” and “His Majesty, The Scarecrow of Oz.”

Still from "The Magic Cloak" featuring Violet MacMillan

A great deal of time and money were invested in the production of the films, with Baum reportedly spending most of his time at the studio. The trade papers declared that no expense had been spared to make the picture “a sensation,” and as the release date approached, a great deal of advertising went into promoting it and the talent associated with it (courtesy of Oz Film publicist Frank J. Baum). Paramount even agreed to distribute it. But when the film failed to perform as well as anticipated, Paramount dropped its option to distribute the two films waiting in the wings.

The response to “Patchwork” was a mixed bag. Some declared it wonderful, magical, wholesome entertainment with impressive special effects, while others said that the photography was subpar and the acting was just “fair.” In addition to the poor response, the Motion Picture Patents Company came after Oz (as it did many other independent film companies) with a lawsuit, forcing the company to settle out of court.

The company tried to adapt by releasing non-fairy tale films alongside other features. They joined forces with the Alliance Films Corporation as their distributor and created films under the name Dramatic Features Co., and branched out with films like “The Last Egyptian” and “The Gray Nun of Belgium” (“A tense heart-gripping, soul-stirring drama of the present war in Europe”), but it wasn’t enough. By mid-1915, the Oz Film Manufacturing Co. was no more, and by the end of 1915, neither was the Alliance Films Corporation. The rise of the studio system was already beginning to claim smaller independent companies

Although Baum wisely didn’t invest his own money into the venture (it was well backed by businessmen), it’s believed that the loss took a toll on his health. He passed away in 1919.

Betty Bronson as Peter Pan in the 1924 film

Unfortunately, it seems that Baum’s biggest mistake was being an independent ahead of his time. Although a lot of comedies could be accessible to kids, no one was focusing on making films specifically targeting young viewers. In fact, fantasy films themselves took a while to catch on. In 1914 and 1915, the biggest box office draws were epic, realistic and sexually or morally controversial films. “The Birth of a Nation,” “Judith of Bethulia,” “A Fool There Was,” “The Golem,” two versions of “Carmen,” “The Cheat,” and “Cabiria” were all released in those two years, and all are vastly different from what Baum was offering. Of course, a few years later, fantasy and fairy tale stories were accepted and enjoyed by audiences in the form of Douglas Fairbanks’ “Robin Hood,” “The Thief of Bagdad,” and “Peter Pan” (with J.M. Barrie himself having final say over who would play the title role).

By the time the definitive film version of “The Wizard of Oz” was released, Baum had been gone for 20 years and the previous versions (except for Larry Semon’s strange adaptation) were largely forgotten. Thanks to the wonders of DVD, many of these versions have found a new life. Curious for more? You can watch “The Patchwork Girl of Oz” below.