This post was

originally published on the lonelybrand blog as part of an ongoing silent film series.

When you think of Chicago, chances are good that the musical and probably the film version of that musical spring to mind. What you might not know, though, is that both are actually based on a play that debuted in 1926, a play that inspired a silent film version the following year.

The characters Roxie Hart and Velma Kelly made their debut in the play “Chicago,” written by Maurine Dallas Watkins. Watkins was a writer for the Chicago Tribune in the early ‘20s and based the characters on two women who dominated the headlines, and whom she had covered for the paper, Beulah Annan and Belva Gaertner respectively. They were involved in unrelated cases, but both women were both charged with shooting and killing their lovers. Incredibly, they were both later acquitted of murder charges.

Beulah Annan and Belva Gaertner (negatives from the Chicago Daily News archives)

Watkins penned the play and it premiered on Broadway in late December 1926 and ran for 172 performances. Hollywood took note and Cecil B. DeMille quickly snapped up the rights (for $25,000 - the equivalent of $320,000 today) to produce a film adaptation and tapping the beautiful Phyllis Haver to play the lead role of Roxie Hart. Although Frank Urson is credited as director, DeMille actually directed most of the film.

Phyllis Haver as Roxie Hart

The story follows Roxie Hart, a gold-digging jazz singer looking to make a name for herself who takes advantage of her husband’s devotion to her. After her lover ends their affair, she shoots him in a state of rage and is terrified that she’ll be tried and put to death. She lies to her husband, saying the man was attempting to rob and violate her, and although he suspects the truth, he agrees to take the blame for her. The fact that Roxie was the killer gets out and the papers are instantly fascinated with her, something that Roxie relishes. The game quickly becomes one of manipulation, presenting Roxie as something she’s not to sway the judge, jury, press and court audience. Although Roxie quite literally gets away with murder, she ends up without a husband, without a home and with nothing but the clothes on her back. Not even the public cares enough to notice her, because they’ve already moved on to the next murderous adulteress.

Previously, Phyllis Haver was with Marie Prevost and Gloria Swanson as one of Mack Sennett’s famous Bathing Beauties. Although the Beauties were famous for their looks, all three went on to prove their talent as true film stars, and Haver’s performance as Roxie remains one of her best. Roxie’s flirty, manipulative, limelight-craving nature endears and disgusts the audience at the same time, and Haver’s performance stands the test of time. When the film was released in late December 1927,

Photoplay hailed her performance, saying, "[T]he picture belongs to Phyllis Haver, who gives a marvelous characterization. We agree with Mr. De Mille that she is his greatest ‘find’ since Gloria Swanson. Of course, nobody will miss seeing ‘Chicago.’”

Roxie and Velma are separated during a cat fight in prison.

This adaptation, as well as the original play version of “Chicago,” later served as inspiration for the 1942 romantic comedy adaptation “Roxie Hart” (starring Ginger Rogers), the 1975 musical stage version and the 2002 film version of the musical. This is even more incredible considering the fact that, for years, the film was thought to be lost. The unstable nature of vintage nitrate films, the frequency of film vault fires and a lack of organized preservation for posterity have all played a part in the loss of many, many films from the silent and early talkie era. In fact, Martin Scorsese’s Film Foundation estimates that over 90% of the films made before 1929 have been lost forever. But, as copyrights expire, and time goes by, some “lost” films are being rediscovered and restored. Such is the case with “Chicago.” Incredibly, a perfect print of the film was discovered in DeMille’s archives, and in 2006, the UCLA Film and Television Archive restored and released the print.

Interested in seeing more? Check out

the entire film, courtesy of Fandor.

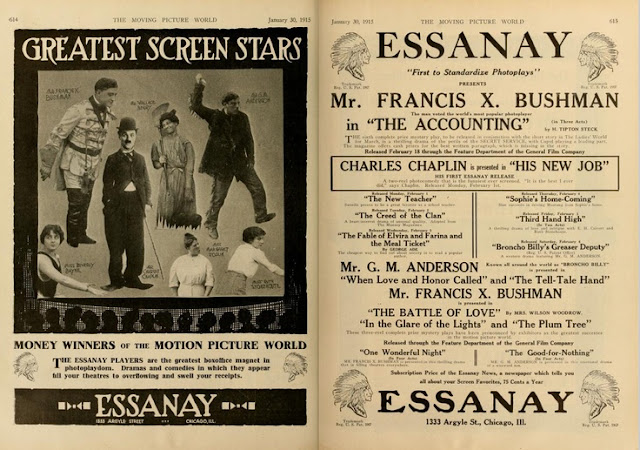

Chicago served as more than just the backdrop for Roxie Hart’s run-ins with the law. During the early days of silent film, it was the home of many major film studios, and even briefly served as

Charlie Chaplin’s home. Learn more about

Chicago’s silent film past.

_01.jpg)

_01.jpg)